A Rumination from my dramaturgy of Steven Dietz’s This Random World directed by David Lee-Painter.

I find myself returning….

This spring I got to attend a wonderful production of TRW at Post Falls High School directed by Payton Edwards. Then last week, digging through some records I found the introductory note I’d written for my dramaturgy packet. The note is below. I rather enjoy that TRW is never far from me to prod me into reflection.

One of the things that immediately struck me about Dietz’s script is how much we miss when we’re narrowly focused on our own lives. We’re not even aware of all the parts we play in other people’s lives–Even some people we never meet. But with a slight shift of our gaze, we might see different things or things as if new—in ways we’ve never looked at them before.

The idea of randomness resonated. We, as creatures on this planet, are trying to control our world and that belief of control can be very important. It can be humbling to discover how much is really just randomness or dumb luck at work.

The second title or subtitle of the play is: The myth of serendipity. Myth is commonly thought of as a falsehood when it is actually a truth manifested as story. A narration. This Random World looks for the truth of serendipity. It visits the Forest Where Lies are Revealed where we are brought closer to the truth.

When I began my research, I thought the second title referred to serendipity as a myth. But I’ve come to believe Dietz is using it to comment on the main title. This Random World is the truth of serendipity.

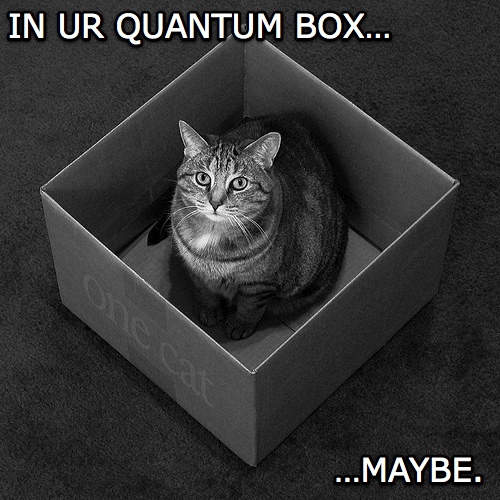

Dietz has crafted a compelling story and at the same time has dismantled it by denying scenes where we expect certain characters to meet. This puts us in & out of the story at the same time—like Schrödinger’s cat. It permits us to study the world he has created and juxtapose it with our own.

As Dietz wrote, one of theatre’s most profound gifts are participation and reflection. And This Random World gives us plenty of opportunities to do that.

Notes on games of chance...

The Drunkard’s Walk: How Randomness Rules Our Lives is a 2008 popular science book by Leonard Mlodinow. It became a New York Times bestseller and a New York Times notable book. It is a book about humans’ ability to create patterns—even when the patterns are not there. Adapted as a survival skill, our pattern-making is not infallible and at times can lead one to the wrong conclusions.

Some of the main lessons:

- We wrongly over-attribute successes and failures to people’s actions rather than luck’s role.

- We should judge people by their character and talents rather than their results.

- We are not as in control as we think.

- What IS in our control is the opportunities we take advantage of and how we improve our own skills toward the best odds.

Along with the aforementioned book, Mlodinow has written for the New York Times about randomness and the human need to feel in control:

We should judge people by their character and talents rather than the results of their efforts.

Randomness causes much of success and failure, and much of that is outside our control. What is in our control is the number of opportunities we take advantage of and how we cultivate our own skills to give us the best odds.

Along with the aforementioned book, Mlodinow has written for the New York Times about randomness and the human need to feel in control:

“What Are the Odds?”

It struck me then that I have Hitler to thank for my existence, for the Germans had killed my father’s wife and two young children, erasing his prior life. And so were it not for the war, my father would never have emigrated to New York, never have met my mother, also a refugee, and never have produced me and my two brothers … The outline of our lives, like the candle’s flame, is continuously coaxed in new directions by a variety of random events that, along with our responses to them, determine our fate.

REFERENCES

Mlodinow, Leonard. The Drunkard’s Walk: How Randomness Rules Our Lives, Vintage Press, 2008.

Mlodinow, Leonard. “The Limits of Control,” New York Times, June 15, 2009.

Mlodinow, Leonard and the Editors. “What Are the Odds?” New York Times, May 22, 2009.