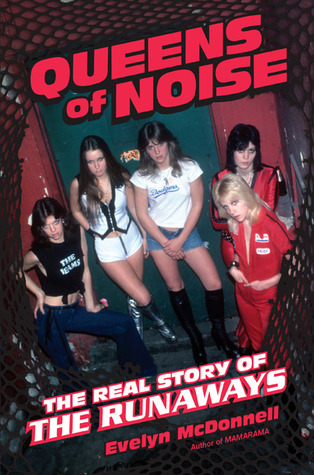

“Queens of Noise the REAL story of the Runaways,” that title is ample warning to the reader for what lies ahead. A sensationalized story about a band of teen rockers. The book is enjoyable in the main and my complaints settle around how McDonnell chose to tell the story of this barrier-shattering group.

Queens of Noise is a follow-up to McDonnell’s thesis on Runaways drummer, Sandy West. For this book McDonnell takes us back again to the Sunset Strip in the 1970s with its proto-punk scene. It was fertile soil for the all-female rock band that Sandy played in. It’s a story that interests me. I grew up with Joan Jett’s music and had heard hints of the fabled band that she started, which included heavy metal guitarist, Lita Ford. I was onboard.

I wanted it to be exhaustive, but the book fell short. Some of the band members declined to be interviewed, forcing McDonnell to rely heavily on previous magazine and newspaper articles, and Vicki Blue’s (another Runaway) documentary, “Edgeplay.” The first-hand accounts come primarily from the Runaways bassists and Kim Fowley, the band’s notorious manager, and the people around the group during the three or so hectic years of its existence.

There was one person I didn’t expect to be included in the Runaways’ story and that was McDonnell. Working primarily in an opinionated style reminiscent of ‘70s New Journalism, she comments on every player in the story even describing a music critic of the day as a “sh*tty writer” without offering anything to back up her opinion. Her subject would have been better served by not inserting herself into the narrative. The block quotes she included from interviews are enthralling and would have been much more effective with only minor editorial comment.

Her description of ‘70s LA evokes a curious version of the sinner/saint idolizing of women that flourished then. It was a dichotomy where few female rock groups could find success. Placing the Runaways in its milieu of the hedonistic Sunset Strip gives clarity. These straightforward passages, untainted by opinion, were where I found some of the best writing.

Before long, McDonnell focused on the Runaways through her own lens of understanding. It is a viewpoint that is not insightful and at times reads like a fan thwarted access to her idols.

She does address the myth that they were a confectionary out of Fowley’s fevered mind. While affirming that the young women created the band with Fowley’s help, McDonnell continually lists everything Kim Fowley did for them.

The band was never allowed to be the subject of its own story but always the object. McDonnell even uses them as objects in her book. She dwells over imagery about Lita Ford’s tight clothes. According to McDonnell, Ford’s shorts were snug enough that part of her reproductive anatomy was in public view. She repeatedly mentions how pretty they were, imagines the reactions of the primarily male audiences, and describes guitarist, Joan Jett’s “sweaty grinding” on a bandmate. These short anecdotes are included for no other reason than prurient interest. One despairs that the Runaways will never be able to run away. Instead they find themselves trapped in another gilded cage to be adored, admired, and defined by others.

Errors or editing gaffs in the book are glaring. For instance, claiming that the Runaways opened for Metallica before Metallica had a formed left me wondering which band she meant. Listing Jett’s role in The Rocky Horror Show as “Columbine” instead of “Columbia.” Strange nouns or verbs muddled what McDonnell wanted to say. Perhaps she too struggled to grasp their meaning? For example, the word “gobbing” or stating Lita playing a “wank” on her guitar. While I can hazard out the meaning, it drug me out of the story. I’m still trying to figure out what a “totem manager” is and if she didn’t mean “token manager.” There were also repetitions of blocks of text in different chapters. A few but not all of Jett’s solo hits that were mentioned did not list the songwriter. The reader is left with the impression that Jett wrote “I Love Rock n’ Roll” and “Crimson & Clover” which is not the case.

The Runaways’ story would have been better served by letting the people who lived it simply tell their stories. As is, Queens of Noise is an impediment with uncited interpretations that cloud a fascinating tale of teens who took the world by storm. Despite the morass, the Runaways and their story managed to get through, much as they did in the ‘70s, demonstrating the wit, the panache, and the perseverance required to bring their sound to the world.