Happy Mess by Ian Paul Messersmith

directed by Sarah Campbell

dramaturgy by Ariana Burns

packet prepared Summer 2020

(Moscow Idaho’s Rotary Park water tower photo by Elaina Pierson)

Happy Mess is in development at the University of Idaho Theatre Arts Department through the Fall 2020 semester.

TOPICS

One of the important moments in Happy Mess is when Bella comes out to her mother when her mother moves back to the family home after being away for several years. Bella is out in other aspects of her life but is almost forty years old when she tells Mama.

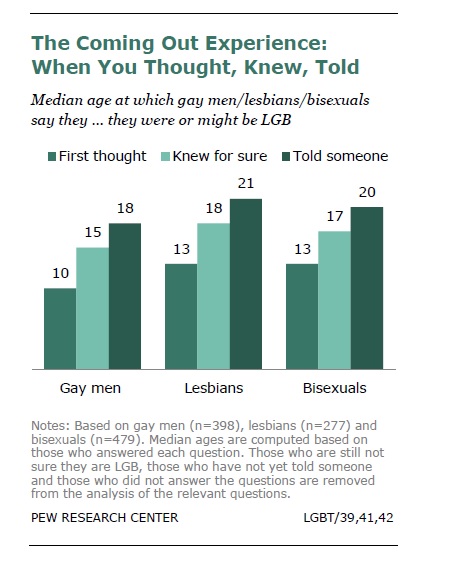

No two coming out stories are the same—a comment often made in the articles about people who came out later in life. Pew Research’s study in 2013 of LGBT+ Americans found that younger adults disclosed their orientation earlier in life that older adults. It anticipated that this was due both to changing social norms and the population itself:

The survey finds that the attitudes and experiences of younger adults into the LGBT population differ in a variety of ways from those of older adults, perhaps a reflection of the more accepting social milieu in which younger adults have come of age.

Pew Research

Tanya Byrne writes about her coming out when she was in her late 30s. She knew she was different but there was no what she called an “A-ha moment.” She attributed this in part to a lack of role models. She also mentioned that coming out is not a one and done event:

I don’t know why people say you ‘come out’ like you do it once then it’s done. I come out pretty much every day. To colleagues, neighbors, friends I haven’t seen for years, to the random bloke at the bus stop who wants my number. Every time I meet someone new, I have to ask myself the same thing: ‘Can I trust you? Are you going to hurt me?’ and that [sic] hope they don’t.

Tanya Byrne

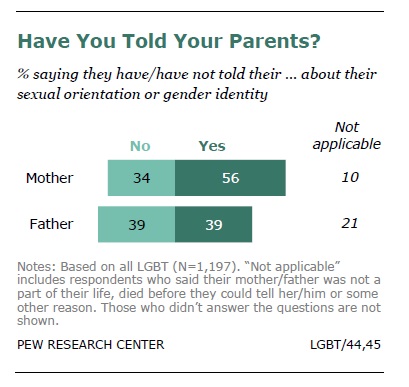

The Pew Research study found that telling parents about their orientation was an important milestone. 56% of respondents had told their mother. 10% in the study the question was not applicable. 39% had not told their father.

Byrne, Tanya. “5 Things I learned about Coming Out at 40. Oct 11, 2017.” https://medium.com/s/5-things-i-learned/five-things-ive-learned-about-coming-out-at-40-by-tanya-byrne-dc0c85dc6236. Last Accessed: August 16, 2020.

Pew Research Center. A Survey of LGBT Americans Attitudes, Experiences and Values in Changing Times. 2013. https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2013/06/13/a-survey-of-lgbt-americans/. Last Accessed: August 16, 2020.

Before moving on, I would note that Miller, writing for the New York Times had to update her article because of the vagueness of being “openly gay.”

This article had been revised to address the uncertain nature of “openly.” Some readers consider openly to include people who are out in their personal lives but not in the workplace; other readers, and the Human Rights Campaign, count only those who publicly identify themselves as gay.

Miller, Claire Cain. “Where Are the Gay Chief Executives?” New York Times. May 16, 2014. https://nyti.ms/1gJLwum. Last Accessed: August 16, 2020.